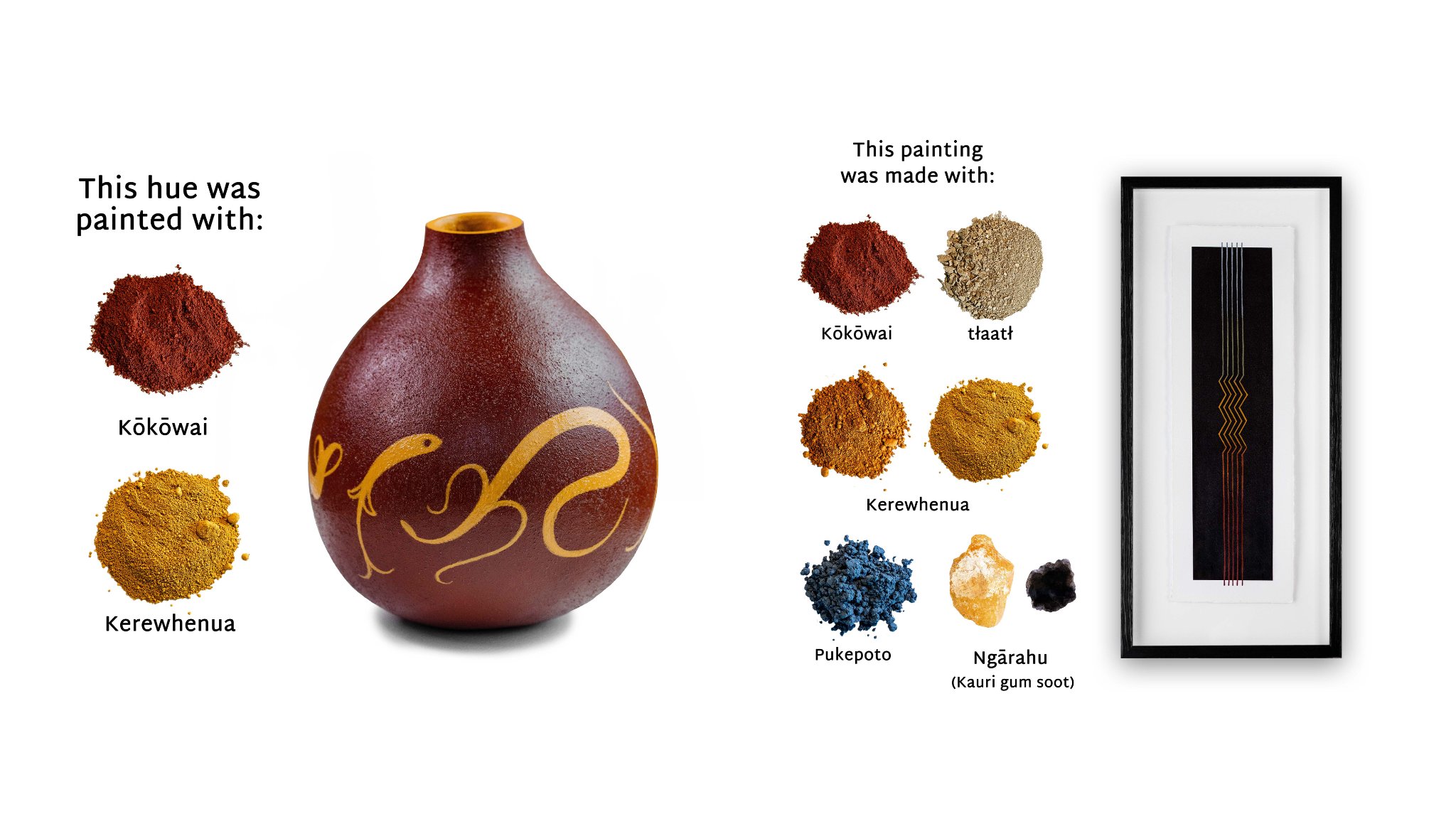

Sian Montgomery-Neutze, Muaūpoko, Ngāi Tara, Ngāti Apa. Hei tuna made with whale sinew, whale bone and earth pigments. © Sian Montgomery-Neutze.

In Honour of Toi Māori

Documenting practitioners and their work as inter-medium reconciliation, Nā Trinity Thompson Brown.

When admiring the form of a toi Māori practitioner in this digital age, it is unlikely we’re engaging directly with their physical work. More commonly, the beholder is engaging with photographs of the artist's work and the accompanying written text explaining its story. Two disciplines that, independently, take years to become highly skilled in.

Many of us are familiar with the trope of the freelancer who must figure out how to do everything on top of their chosen field – how to be a business owner, an accountant, a publicist and so on. Toi Māori practitioners are often faced with another contentious challenge: in order to multiply the lifespan of their work and the number of ways people can engage with it, they have to recreate its form across other disciplines like photography, videography, writing, and design.

Recently, my focus has turned to developing long-term working relationships with a small number of toi Māori practitioners. As a photographer and writer working across both disciplines, I’ve found there’s a gap in the toi Māori photography space of documenting and memorialising the works of practitioners over the course of their careers. Bridging this gap requires building meaningful, high-trust relationships with the right people and the relevant skills in order to showcase, enhance, accurately characterise and honour the skill of the practitioner’s work. All the while, continuing on a parallel path of evolution with our own discipline.

Where does inter-medium reconciliation come in?

The old books of European academics who studied us in the 1800s and 1900s did so with their cameras and their pens. When I look at our own mediums within toi Māori, it always put an uncomfortable mirror up — I wrestled with the tension of knowing that the colonial origins of my mediums were frequently used to mischaracterise, harm and erase. At the same time, I was never brave enough to go back to toi Māori when I had already grown up disconnected; it was easier to choose disciplines outside of my culture and use those as bridges to reconnect.

Photographing toi Māori became my place to land where both of realities could exist easily — a background of disconnection and a journey of reconnection. One of the biggest learning curves with photographing toi Māori has been pivoting my own perspective to avoid coming in with an ego and assuming that there can be an individualist’s monopoly on visual form.

In practice, that means:

- consultations before photoshoots (this is also the time I’ll say no if I don’t think I’m able to fulfill their vision)

- reviewing the photos with the practitioner mid-shoot so we can identify early if there’s anything missing or that needs repositioning,

- sending a contact sheet afterwards for the practitioner to select their preferred images,

- intaking multiple rounds of revisions,

- doing reshoots where necessary,

- supplying the final images in a timely manner,

- giving practitioners co- or full ownership of the copyright and explicitly communicating that the jointly created work will not be used without first seeking the practitioner’s permission.

.jpg)

.jpg)

Most of this is standard anyway, and it’s safe to assume Māori photographers practise this instinctively because it’s at the core of maintaining a culturally safe and ethical photographic experience. However, I’ve reiterated it here because working with practitioners is largely defined by holding the process gently. A successful relationship between the toi Māori practitioner and the photographer is about knowing whose lane is whose. The photographer may know their toolkit best, but they don’t know the practitioner’s work, story or commitment to craft better than the practitioner does.

The most common reaction I’ve had to this approach has been surprise – being able to retain autonomy in how their work is documented has been unexpected, then gladly welcomed. In some cases, it’s just reminding them that I don’t know their work as well as they do and their input is essential to ensuring the final photographs meet their vision. Other times, it’s because of negative experiences with photographers who have assumed all control, given no space for feedback, photographed the works incorrectly, or charged above market-value rates per image. All of these are unfortunately quite common, but the bottom line remains the same: toi Māori practitioners deserve to have access to high-quality representation of their work that they themselves are pleased with and retain control over.

.jpg)

.jpg)

Speaking With, Not Speaking For

Totality of form is often what practitioners need to be represented, even if they don’t say this explicitly. I’ve found the best way to ensure this is to build the process together so that there’s ample room to listen, ask questions about their aspirations and get on the same page about when and how the work will be carried out.

The writing and/or editing usually comes after this and, depending on the artist, it can be anywhere from a light copy edit and a tightening up of the punctuation, to a structural edit. Seeing where the practitioner is communicating meaning for the audience to understand, and enhancing it, is the goal — doing so in a way that still sounds like their voice, but also feels easy, accessible, fluid, conversational and open. When doing this bilingually, it’s important to identify the unique characteristics of their voice across both languages and retain these in the editing process.

Here are some common places where it’s extremely helpful to have a writer and/or editor involved:

- practitioner biography,

- captions on Instagram, Facebook and social media,

- captions in art journals and print media,

- exhibition collateral:

- copy for the placards next to works,

- copy for the exhibition catalogue,

- copy for website display

- copy supplied in English, te reo Māori or both.

- funding applications and summary reports.

Involving a writer and/or editor here can be hugely beneficial. It can help make aspects of work feel more approachable, whether that’s biographies for artist panels, or cover letters and deliverables for funding applications. It is also a way writers can give back to the toi Māori community who so generously and considerately holds the revival of our culture’s art forms in their hands and minds. Inter-medium collaborations aid everyone by broadening our appreciation of each others’ commitments to our chosen disciplines.

.jpg)

In my eighth year as a photographer, I’ve finally found my place in the Māori arts ecosystem where it all makes sense – photographing and writing in honour of toi Māori, and the practitioners who look after them. We have so much to give each other that will collectively enhance our own practices and the ways we represent, and speak to, each other’s works.

Nō reira, ka nui te mihi ki ngā tauira, ki ngā ringatoi me ngā mātanga o Te Ao Toi Māori me ōna tini āhuatanga. Here’s to toi Māori and the generations of practitioners who fought to bring it back from the brink of cultural extinction, into the renaissance we now all benefit from.

Ka nunui te mihi ki a Sian Montgomery-Neutze rātau ko Vianney Parata, ko Ngahina Hohaia, ko Rangi Kipa e whakarangatira nei i tēnei tuhinga nā ō rātau mahi toi.

.jpg)

Trinity Thompson-Browne, Ngāti Kahungunu, Muaūpoko, is a poet, writer and photographer based in their ancestral lands of Te Whanganui-a-Tara. Their current photographic work focuses on documenting a small number of toi Māori practitioners and the evolution of their practices.

Thompson-Browne was a finalist in the biennial Kiingi Tuheitia Portraiture Award 2023 for their visual poem, searching for haana hirini, a triptych about trying to find their ancestor where colonisation had blurred the lines back to them.

Thompson-Browne is a three-time programmer for Verb Wellington Readers and Writers Festival on behalf of Te Hā o Ngā Pou Kaituhi Māori. They hold a BA majoring in Applied Linguistics and Te Reo Māori from Te Herenga Waka and a Graduate Diploma in Publishing from Whitireia. Their debut, three-volume poetry collection i am navigator has been produced independently by an uninterrupted chain of Māori hands over seven years and comes out late 2024.